What is behavior and what does it mean for psychologists?

Contents

What is behavior and what does it mean for psychologists?¶

Behavior - the what, how, why and when¶

We can think of behavior as relatively fast changes in the spatiotemporal position of an organism in the environment. Behavior is what allows individuals to move, navigate and interact with their surroundings, and helps them adapt to changing environments on a timescale much faster than natural selection. From an ecological perspective, behavior may be considered a selection for flexibility.

The biological study of animal behavior is called ethology (see Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch), while psychologists may approach similar questions from perspectives like behavioral ecology or comparative cognition.

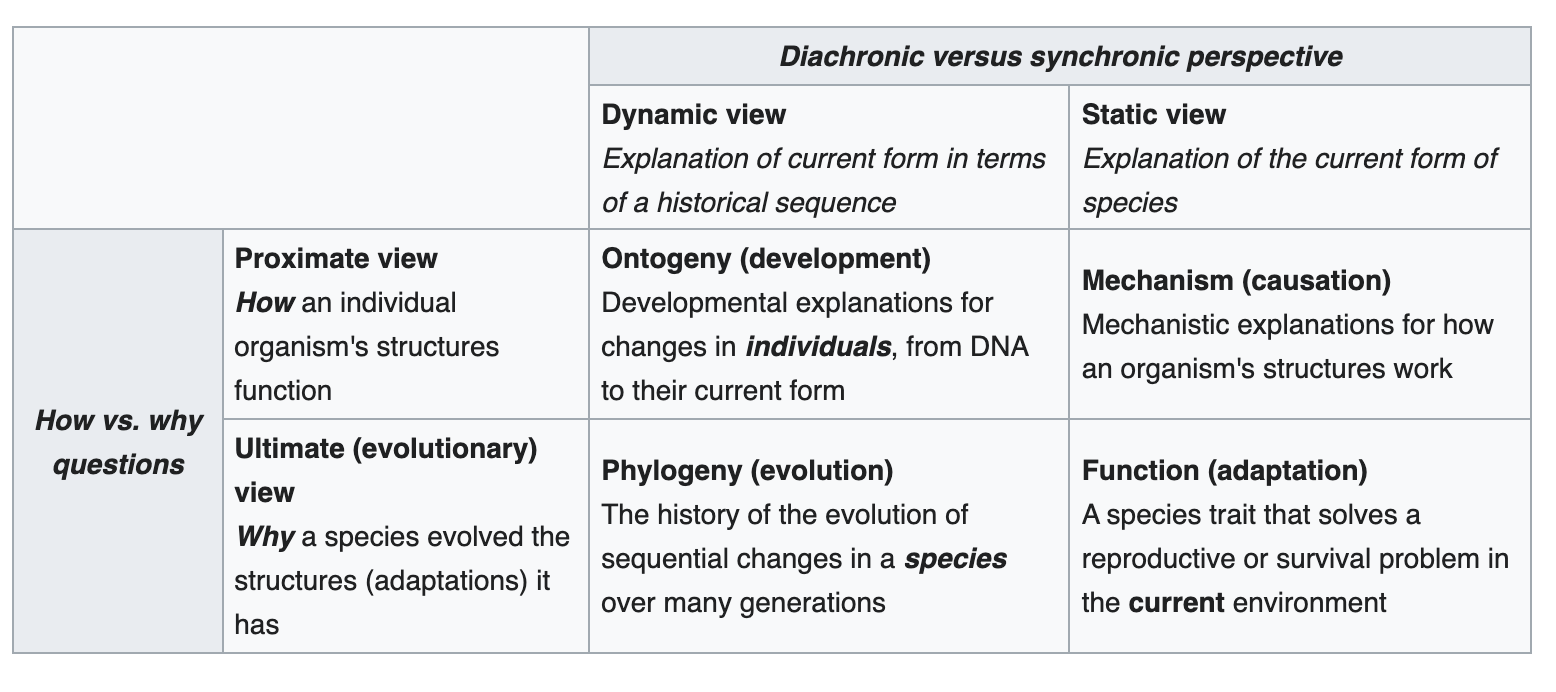

In his On Aims and Methods of Ethology, Tinbergen lays out four specific questions or levels of analysis to be used for a complete study of behavior (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Tinbergens’ four levels of analysis, from Wikipedia.¶

Definitions of Behavior¶

Some of the most common definitions of behavior among behavioral biologists:

Davis (1966): What an animal (or plant) does.

Tinbergen (1955): The total movements made by the intact animal.

Raven & Johnson (1989): Behavior can be defined as the way an organism responds to stimulation.

Wallace et al. (1991): Observable activity of an organism; anything an organism does that involves action and/or response to stimulation.

Beck et al. (1991): Externally visible activity of an animal, in which a coordinated pattern of sensory, motor and associated neural activity responds to changing external or internal conditions.

Starr & Taggart (1992): A response to external and internal stimuli, following integration of sensory, neural, endocrine, and effector components. Behavior has a genetic basis, hence is subject to natural selection, and it commonly can be modified through experience.

Grier & Burk (1992): All observable or otherwise measurable muscular and secretory responses (or lack thereof in some cases) and related phenomena such as changes in blood flow and surface pigments in response to changes in an animal’s internal and external environment.

Accepted statements about behavior (by majority vote, see Levitis et al. 2009):

‘A developmental change is usually not a behavior.’

‘Behavior is always influenced by the internal processes of the individual.’

‘Behavior is something whole individuals do, not organs or parts that make up an individual.’

‘A behavior is always in response to a stimulus or set of stimuli, but the stimulus can be either internal or external.’

Rejected statements about behavior (by majority vote, see Levitis et al. 2009):

‘Behavior is always in response to the external environment.’

‘A behavior is always an action, rather than a lack of action.’

‘People can all tell what is and isn’t behavior, just by looking at it.’

‘Behavior always involves movement.’

‘Behaviors are always the actions of individuals, not groups.’

‘In humans, anything that is not under conscious control is not behavior.’

‘Behavior is always executed through muscular activity.’

Disagreement defining Behavior¶

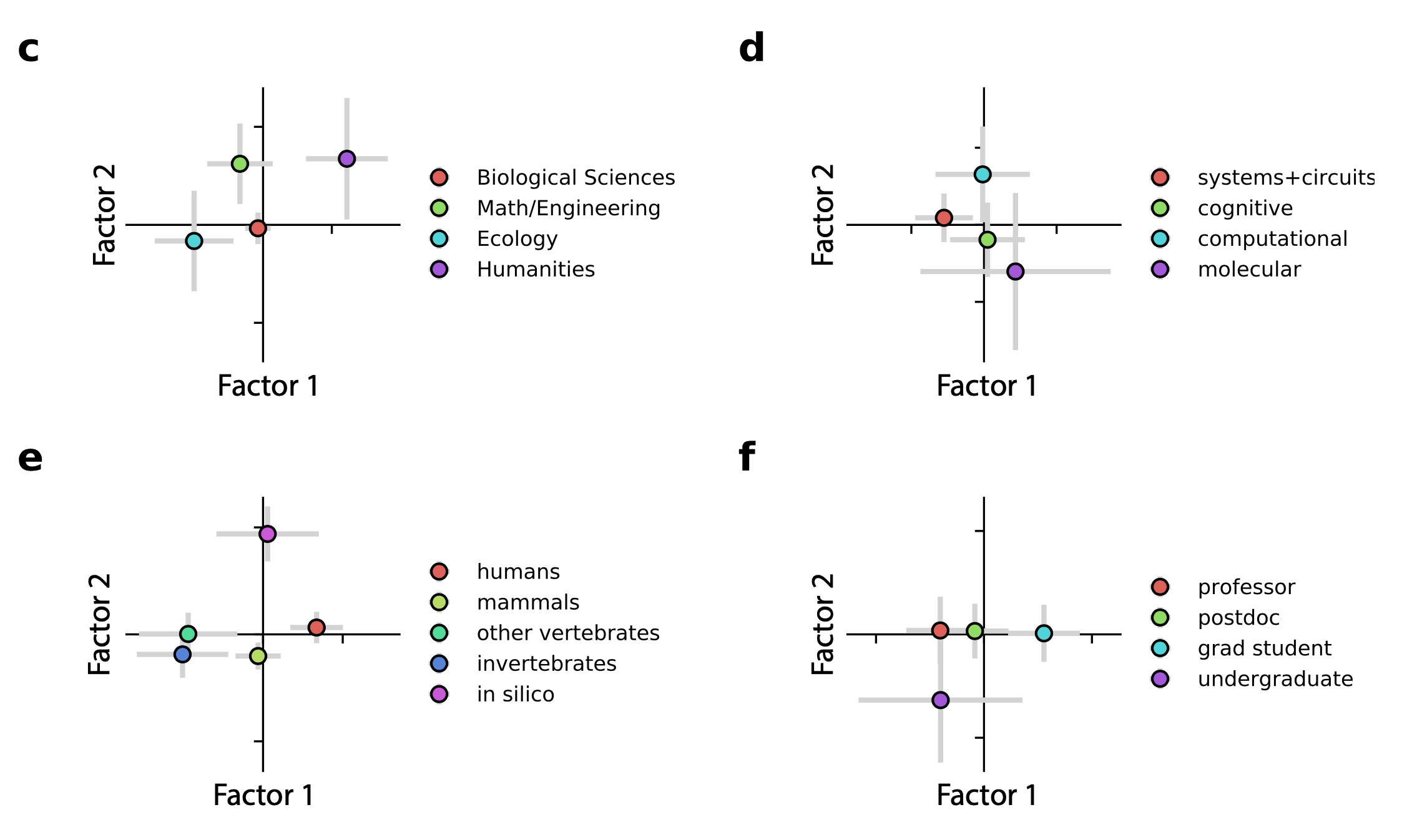

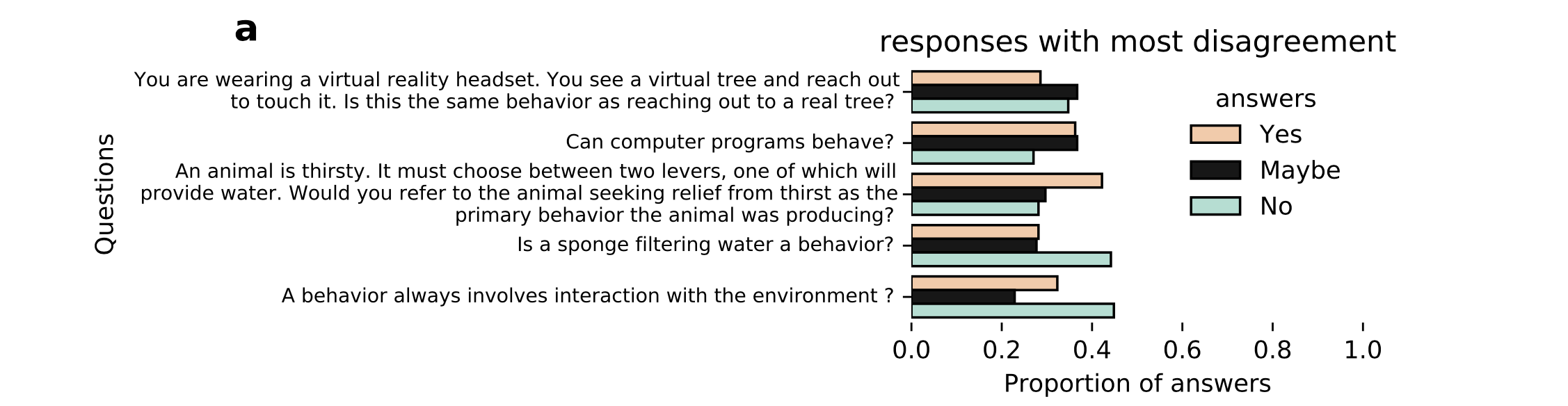

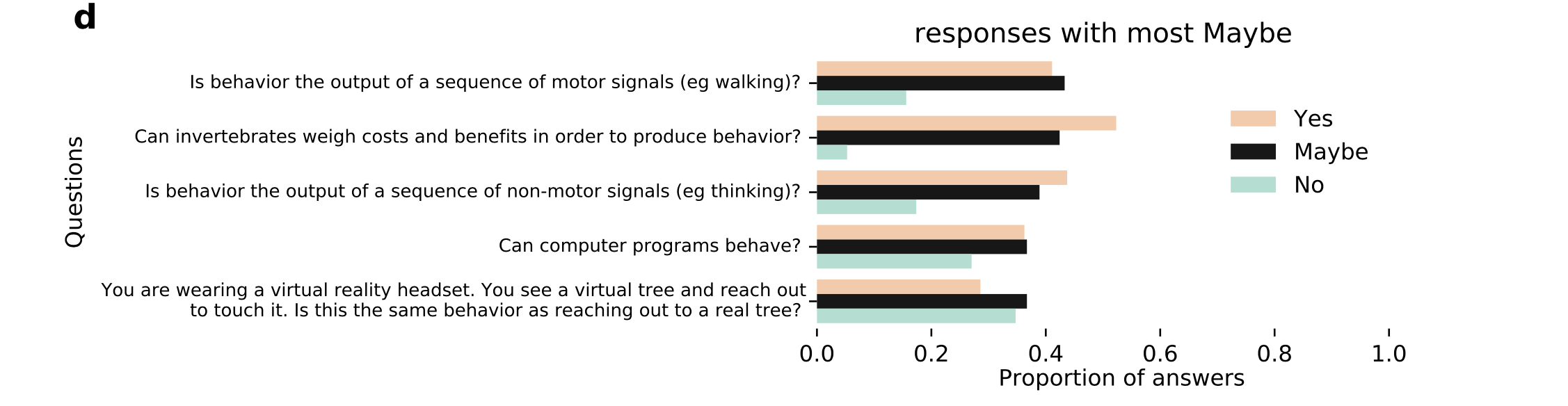

In their preprint, Calhoun and Hady (2021) develop a survey about what scientists in different disciplines really understand by behavior. As expected from Levitis et al. (2009), they find high disagreement between groups in their views of what does and what doesn’t constitute behavior, but most interestingly they identify stable response clusters to different qualitative definitions of behavior. In Fig. 3 the different clusters indicate consistent differences among disciplines, sub-disciplines of neuroscience, as well as model organism and academic seniority.

Fig. 3 Disagreement defining behavior, from Calhoun & Hady, 2021.¶

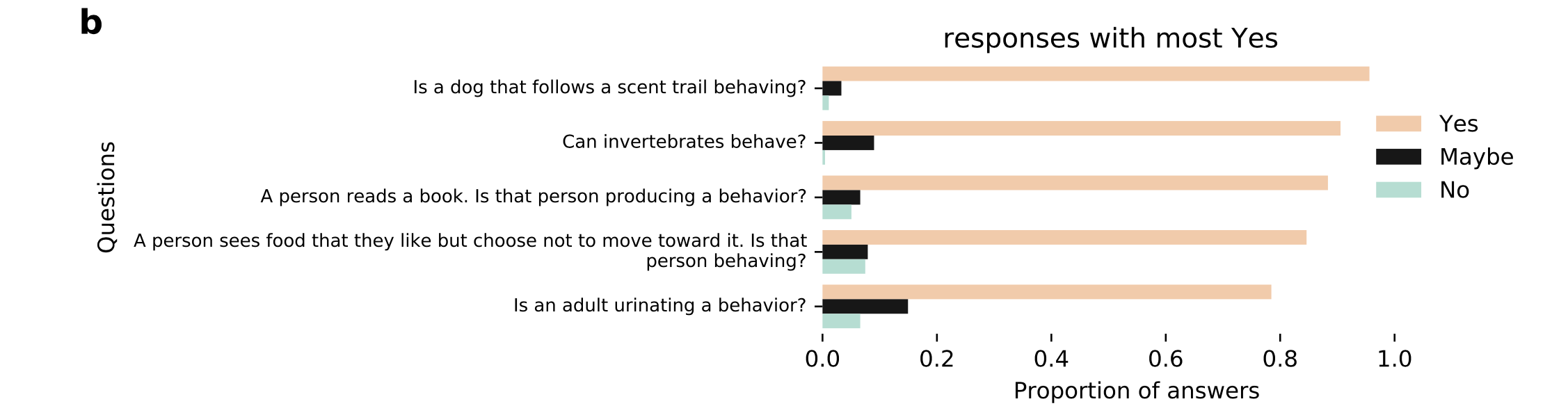

Most agreed upon statements:

Fig. 4 Agreement to behavior questions, from Calhoun & Hady, 2021.¶

Fig. 5 Agreement to not-behavior questions, from Calhoun & Hady, 2021.¶

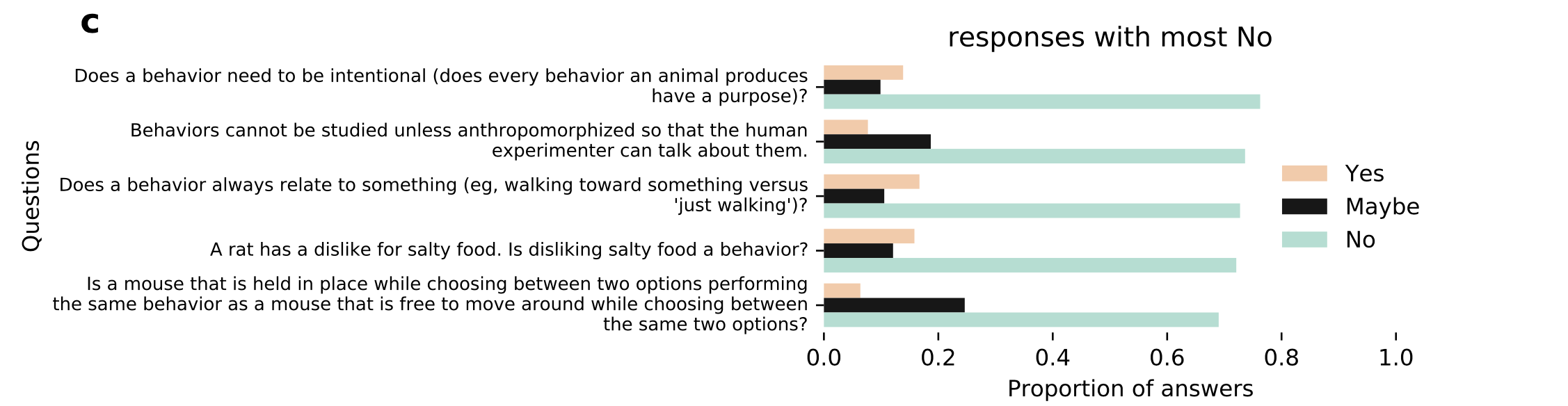

Most disagreed upon statements:

Fig. 6 Disagreement to behavior questions, from Calhoun & Hady, 2021.¶

Fig. 7 Disagreement to behavior questions, from Calhoun & Hady, 2021.¶

Behavior for Psychologists¶

Psychologists are primarily interested in behavior as a proxy (observable, quantifiable output) for internal processes in the model organism. Almost all areas of psychology are interested in some sort of behavior: be it during developmental processes, typical behavioral traits (personality), economic decision-making, healthy habits or clinically relevant behavioral disorders. Even cognitive testing relies on behavioral responses to items or stimuli presented (be it speech or non-verbal key-pressing). And most research areas of neuropsychology with a direct insight into neural activity try to link these cognitive phenomena to real-world behavior.

The disagreement in what exactly constitutes behavior among psychologists seems to rely more on the model organism and specific research area under investigation, than on any other difference among disciplines. A clinical psychologist may refer to a prolonged pattern of maladaptive human habits as behavior, while a biopsychologist may be thinking about reaction times and key-pressing behavior.

Behaviorism and Cognitivism¶

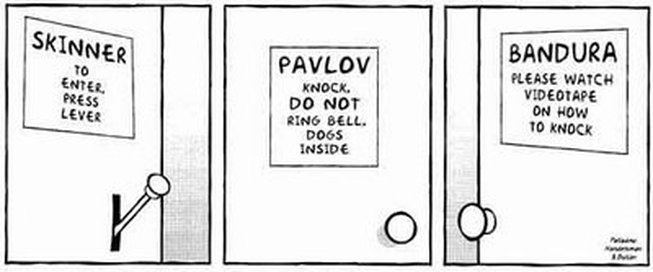

Fig. 8 Behavior and Learning for behaviorists and cognitivists.¶

The disagreement between schools of thought such as behaviorism and cognitivism have shaped the history and development of today’s psychology, but they seem to disagree more on how behavior emerges (genes, reinforcement, internal processes) and how it is learned, rather than on what exactly behavior is.

In psychology, behavior seems to be a construct dependent on its operationalization. And as such, one should describe the respective behavior of interest as detailed as possible.

We can concluded that a closer look at behavior should differentiate between dimensionalities of behavior, from short behavioral motifs to short actions and large-scale behavioral patterns. Furthermore, we may find it useful to distinguish between the structure, the consequences and the spatial relation of behavior.

Literature¶

Calhoun, A., & Hady, A. E. (2021). What is behavior? No seriously, what is it? [Preprint]. Animal Behavior and Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.04.451053

Levitis, D. A., Lidicker Jr, W. Z., & Freund, G. (2009). Behavioural biologists do not agree on what constitutes behaviour. Animal behaviour, 78(1), 103-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.018

Bonus: Ronald Fisher (Victoria University of Wellington)¶

The beginnings of psychology & ethology