Introduction to Computational Ethology#

Behavior - the what, how, why and when#

We can think of behavior as relatively fast changes in the spatiotemporal position of an organism in the environment. Behavior is what allows individuals to move, navigate and interact with their surroundings, and helps them adapt to changing environments on a timescale much faster than natural selection. From an ecological perspective, behavior may be considered a selection for flexibility.

The biological study of animal behavior is called ethology (see Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch), while psychologists may approach similar questions from perspectives like behavioral ecology or comparative cognition.

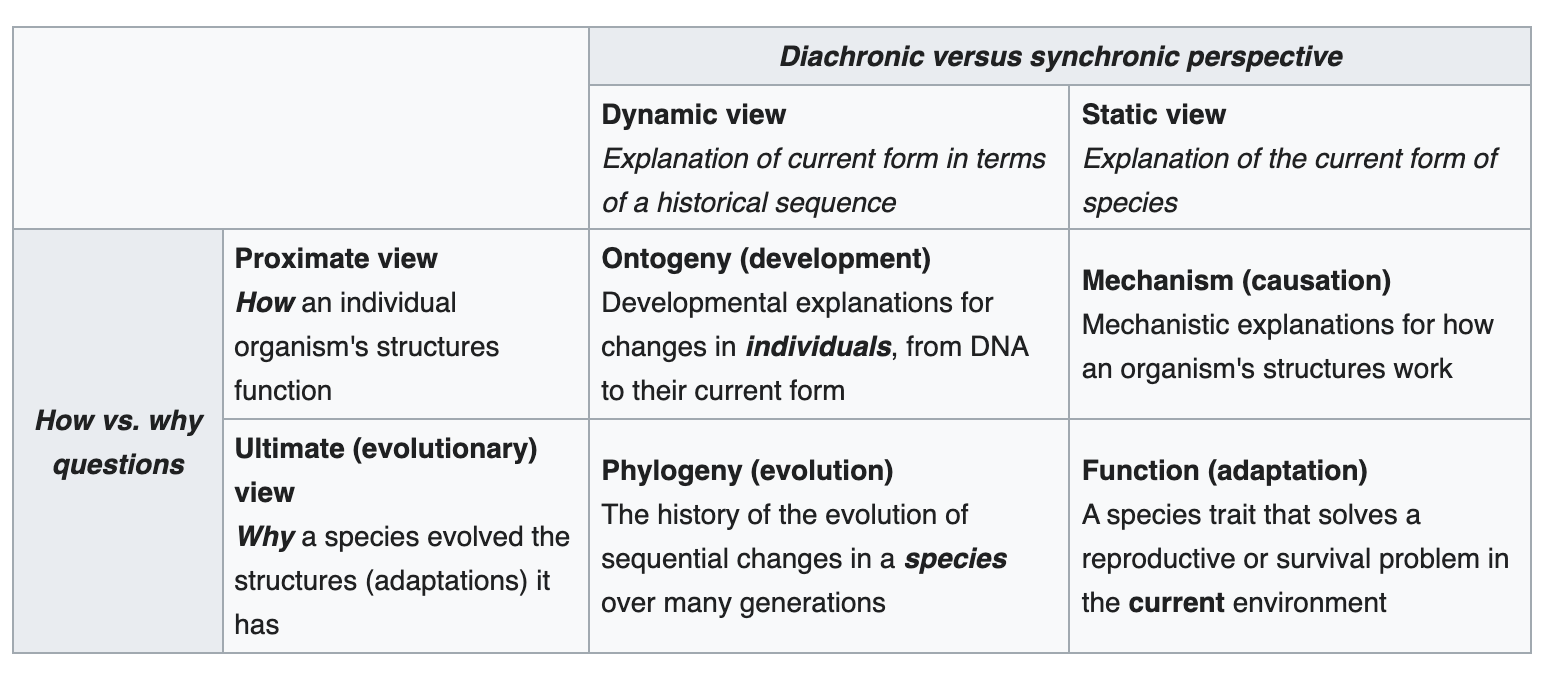

In his On Aims and Methods of Ethology, Tinbergen lays out four specific questions or levels of analysis to be used for a complete study of behavior (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Tinbergens’ four levels of analysis, from Wikipedia.#

Measuring Behavior#

The study of behavior started with rich, naturalistic observations of animals in their natural environments. But these observations were mostly qualitative and anecdotal descriptions, rather than quantitative measurements of behavior (see George Romanes’ Animal Intelligence and Desmond Morris’ The Naked Ape for such examples).

A more systematic approach to measuring behavior was achieved by using scoring sheets of pre-defined behaviors of interest, and manually logging the occurrence and duration of these behaviors at a given temporal resolution in specific time intervals. This allowed the quantification of behavior with simple statistics such as the frequency, latency and duration of given behaviors, as well as the relative proportion of several behaviors in given environments.

These observations and manual coding techniques are still popular today, although video recording techniques allow to store data, and score behavior from the lab, instead of in the field. Furthermore, computer-assisted tools allow to score behavior frame-by-frame. More on this will be covered in a future session on Levels of Analysis and Quantification of Animal Behavior.

These methods have some obvious downsides:

slow, time consuming and dull

subjective, limited to human vision and language

low-dimensional

Specifically, one of the main problems for Psychology and Neuroscience is that the measurement of behavior is by far not as accurate as advances in neural recording techniques such as electroencephalography, optogenetics, pharmacogenetics or optical imaging. How are we then supposed to match cognitive and neural processes to the animals behavioral output?

Computational Ethology#

Computational ethology is a new interdisciplinary field using modern advances in machine learning and machine vision (computational) for measuring, describing and analyzing natural behavior in freely moving animals (ethology).

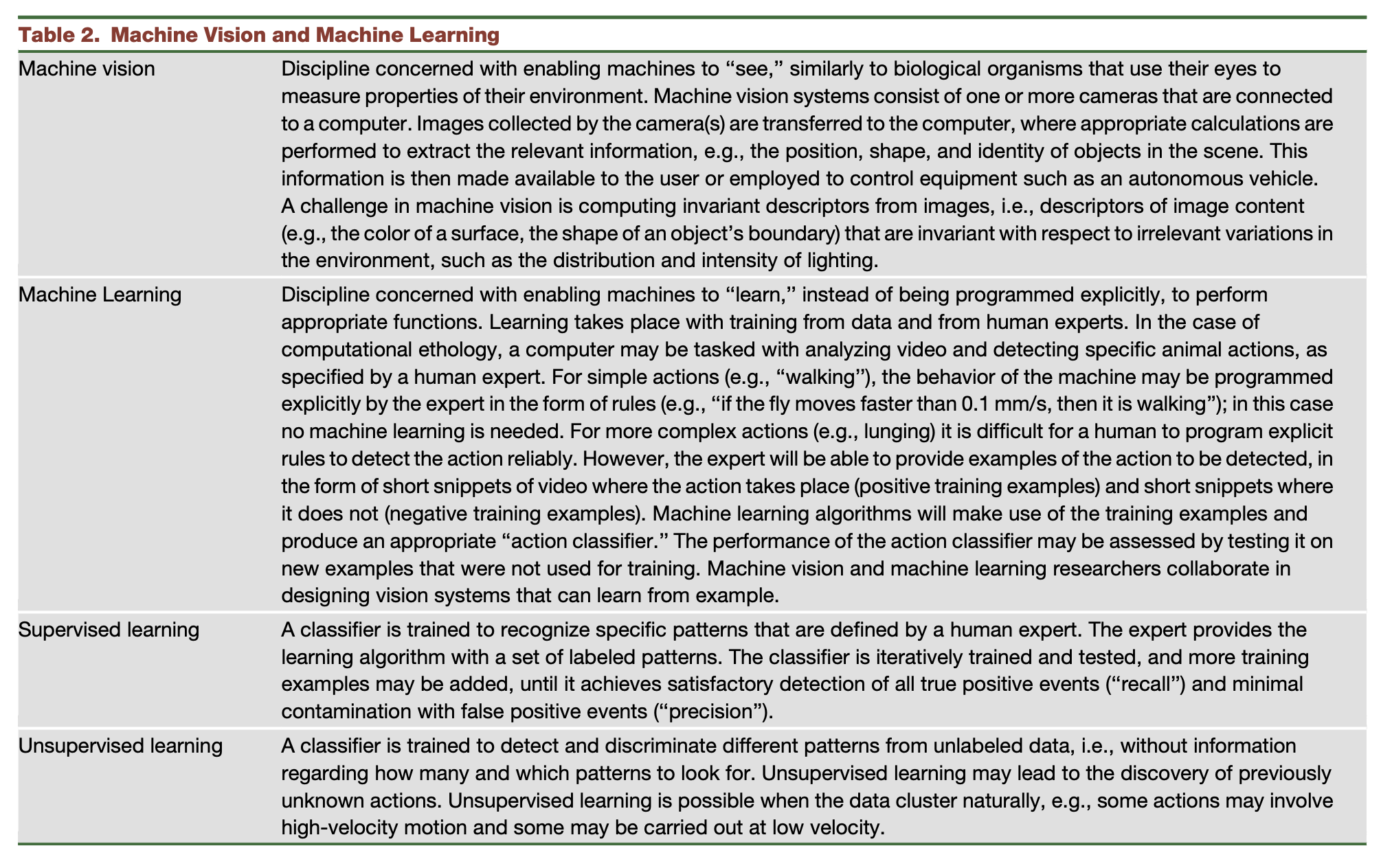

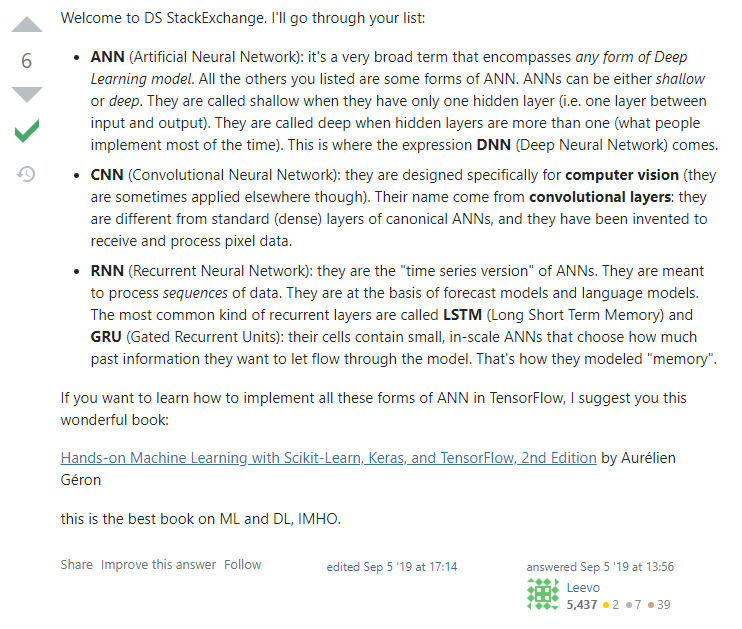

Take some time to get familiar with the computational part of the seminar. In Fig. 3 you can find basic concepts needed to understand the main technological advances in the field. And in In Fig. 4 you will see a very general distinction between the most popular neural networks used in computational ethology.

Fig. 3 Key ML terminology, from Anderson & Perona (2014).#

Fig. 4 Key ML models, from Stack Overflow.#

For a more in-depth understanding of machine learning techniques feel free to ask the internet or brows the online materials for the Computational Neuroscience course from the Neuromatch Academy.

Promises#

By successfully and skillfully applying machine learning methods the study of behavior will profit from a more accurate quantification of behavior, while outsourcing the painstaking manual labor of video coding. Computational models will increase the throughput of behavioral experiments by tracking multiple subjects at once, measuring over prolonged time windows, or even in real time. Real time measurements, in turn, pose new possibilities to design closed-loop experiments reactive to subjects’ behavior.

Computational methods will also increase the dimensionality of behavior, differentiating between short actions and large-scale behavioral patterns, and setting time-accurate context to subjects behavior in the environment.

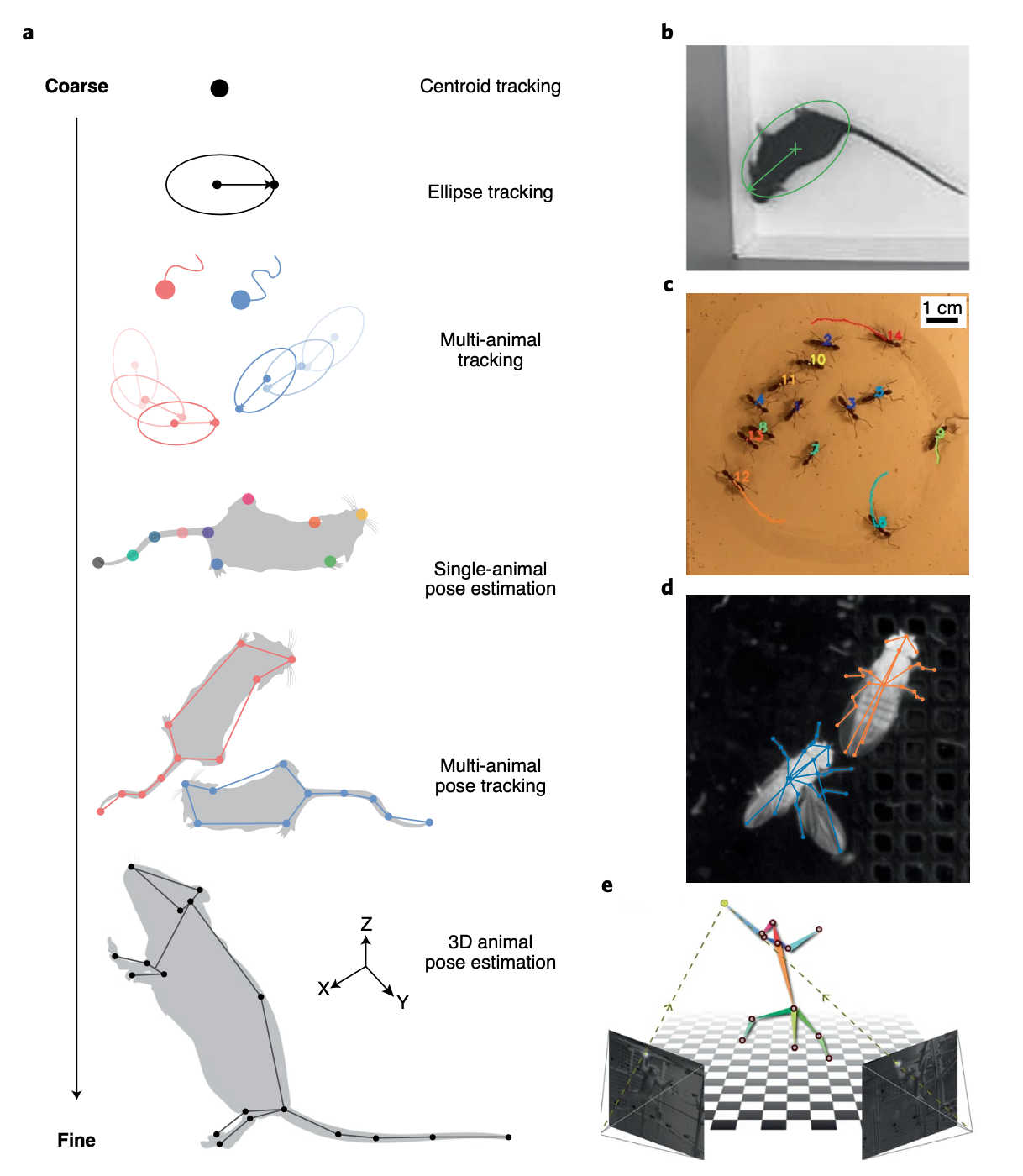

Lastly, specific advances in computer vision revolutionize the way we operationalize the behavior of subjects. See Fig. 5 for an overview of different levels of detail in the tracking of subjects movement.

Fig. 5 Levels of detail in Computational Ethology, from Pereira et al (2020).#

Methods#

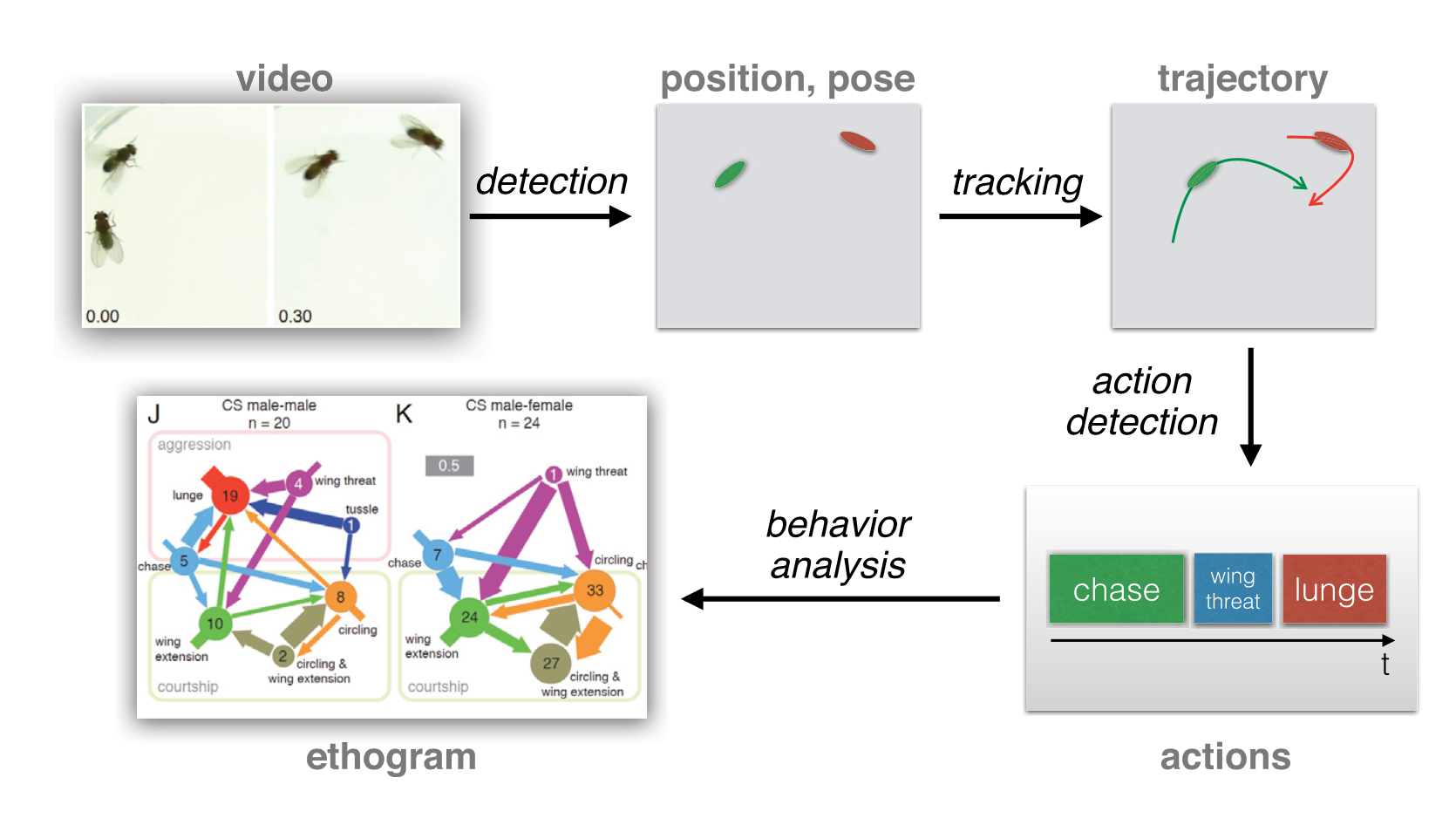

In Fig. 6 Anderson & Perona (2014) give an overview of different steps required for a complete system for the measurement of behavior. Try to get familiar with these steps and understand the main differences among them using the keywords below.

Fig. 6 Steps in typical computational ethology systems, from Anderson & Perona (2014).#

Tracking#

detection

location/position

orientation

centroids, ellipses and poses

trajectory

identity

Action classification#

supervised

unsupervised

ground truth

segmentation

clustering

Behavior analysis#

ethogram

large-scale patterns

behavior systems

discrete and continuous structure

Difficulties#

A new, tech-savvy generation of students is needed willing to cooperate in interdisciplinary teams of biologists, psychologists and computer scientists

3D tracking needs multiple cameras and triangulation, or specialized depth sensors to capture a complete picture of behavior. Skeleton vs surface?

Generalization: specialized trackers for specific individuals, many methods and no standards, machine teaching is still time consuming, transfer learning, active learning, self-supervised learning

Discovery: handcrafted criteria, supervised machine learning, new behaviors, unsupervised learning

Describing Behavior#

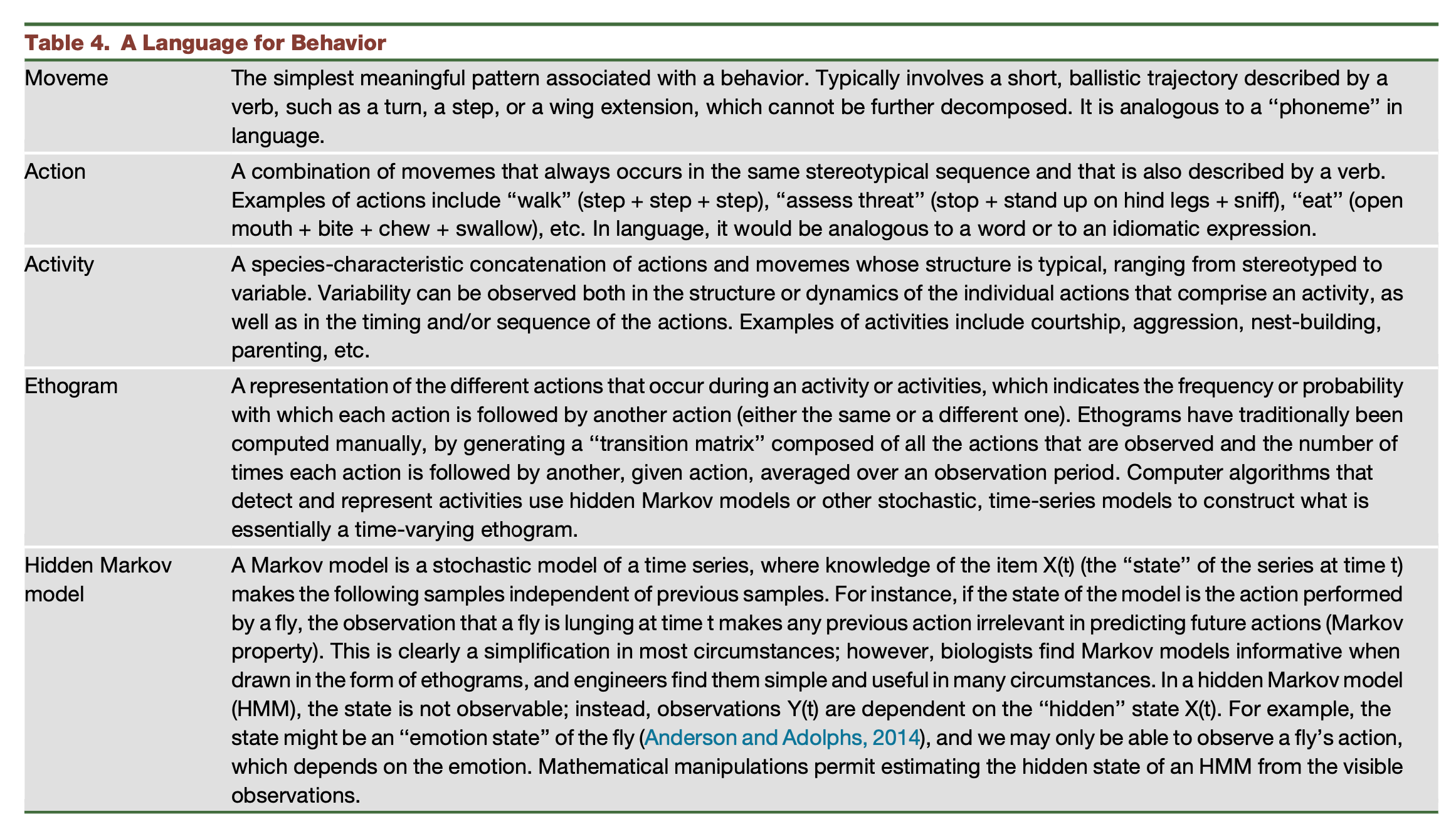

Working on a new understanding of behavior quantification will need a standardized language to describe behavior. Lets get started with Fig. 7:

Fig. 7 Basic terminology for computational ethology, from Anderson & Perona (2014).#

Literature#

Anderson, D. J., & Perona, P. (2014). Toward a Science of Computational Ethology. Neuron, 84(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.005

Pereira, T. D., Shaevitz, J. W., & Murthy, M. (2020). Quantifying behavior to understand the brain. Nature Neuroscience, 23(12), 1537–1549. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00734-z

Bonus: Ronald Fisher (Victoria University of Wellington)#

The beginnings of psychology & ethology