Levels of Analysis and Quantification of Animal Behavior#

So far, we have seen that new technological advances allow computational ethologists to record more and better data, e.g., with wireless sensors for gps or accelerometry, as well as higher resolution and automated video recordings. This helps achieving a higher throughput in experiments and even permitting the observation of new timescales for very short or very long observations.

But how do we make sense of all of this data? We have seen in the previous lectures that we lack an intuitive, easy solution to investigate behavior as a whole, and we often need to narrow our focus to certain definitions of behavior, certain behaviors of interest, or even certain aspects of behavior.

Quote

“The main challenge confronting behavioral science is extracting meaning from an ever-increasing amount of information” - Gomez-Marin et al., 2014

Levels of Analysis and other considerations#

The specific level of analysis should always be referred to, together with the working definition of behavior in general and specific. Does the given behavioral analysis focus on whisker movement in a head-fixed mouse? Or does it focus on the entire body and locomotion behavior? Or even exploration behavior relative to the environment? Or interacting with a conspecific? Or social behavior in a group of mice? Or the collective nest building behavior of a colony? The level of analysis is closely related to the unit of observation and to the unit of analysis. Although these concepts sometimes used interchangeably in different sciences, we will use the term level of analysis to refer to the set of events or phenomena we are interested in and could be enclosed in a single experimental trial.

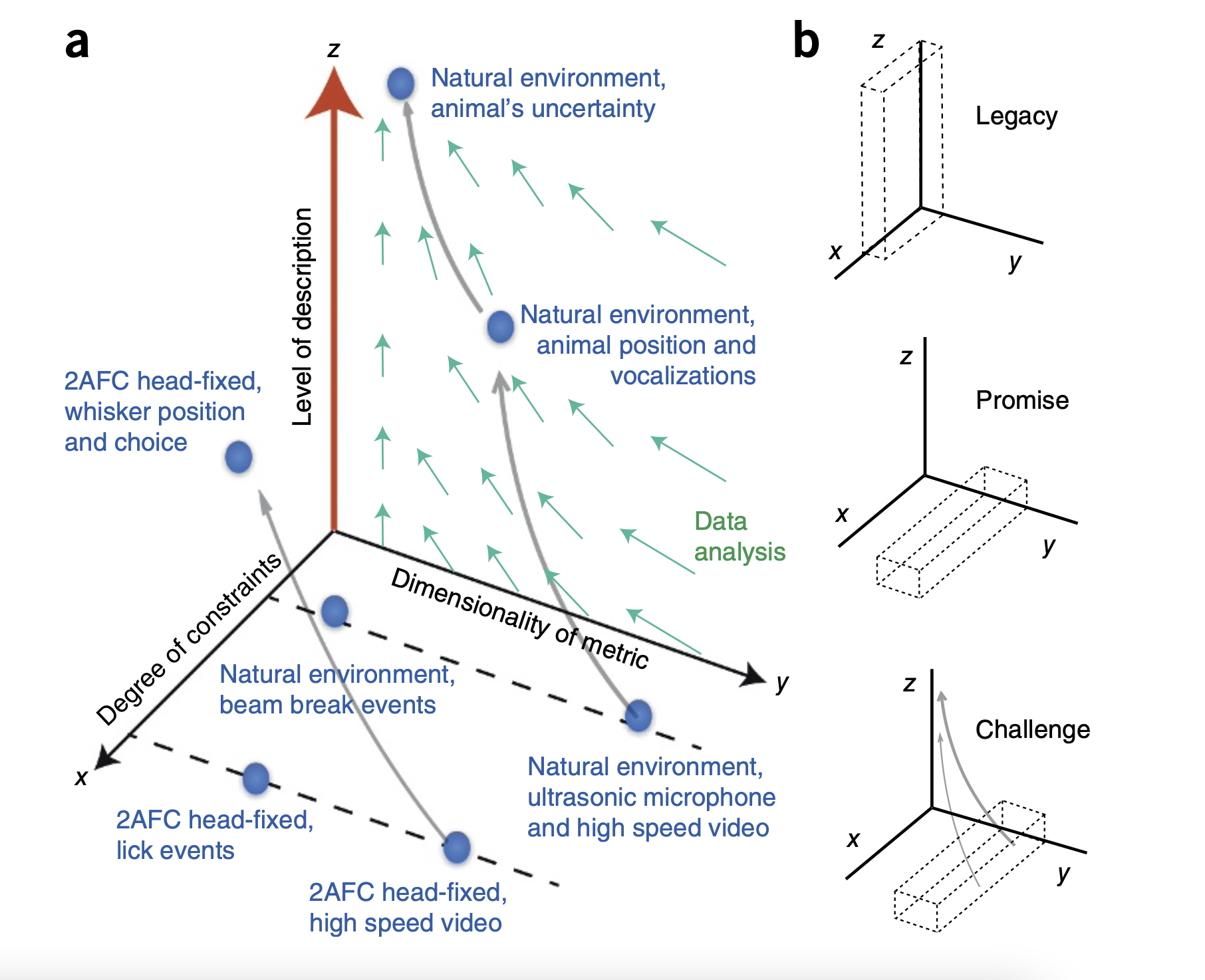

Fig. 14 Dimensionality of measurement, level of description and degree of constraint in behavioral science, from Gomez-Marin et al., 2014.#

Exercise: What is a meaningful unit of behavior?#

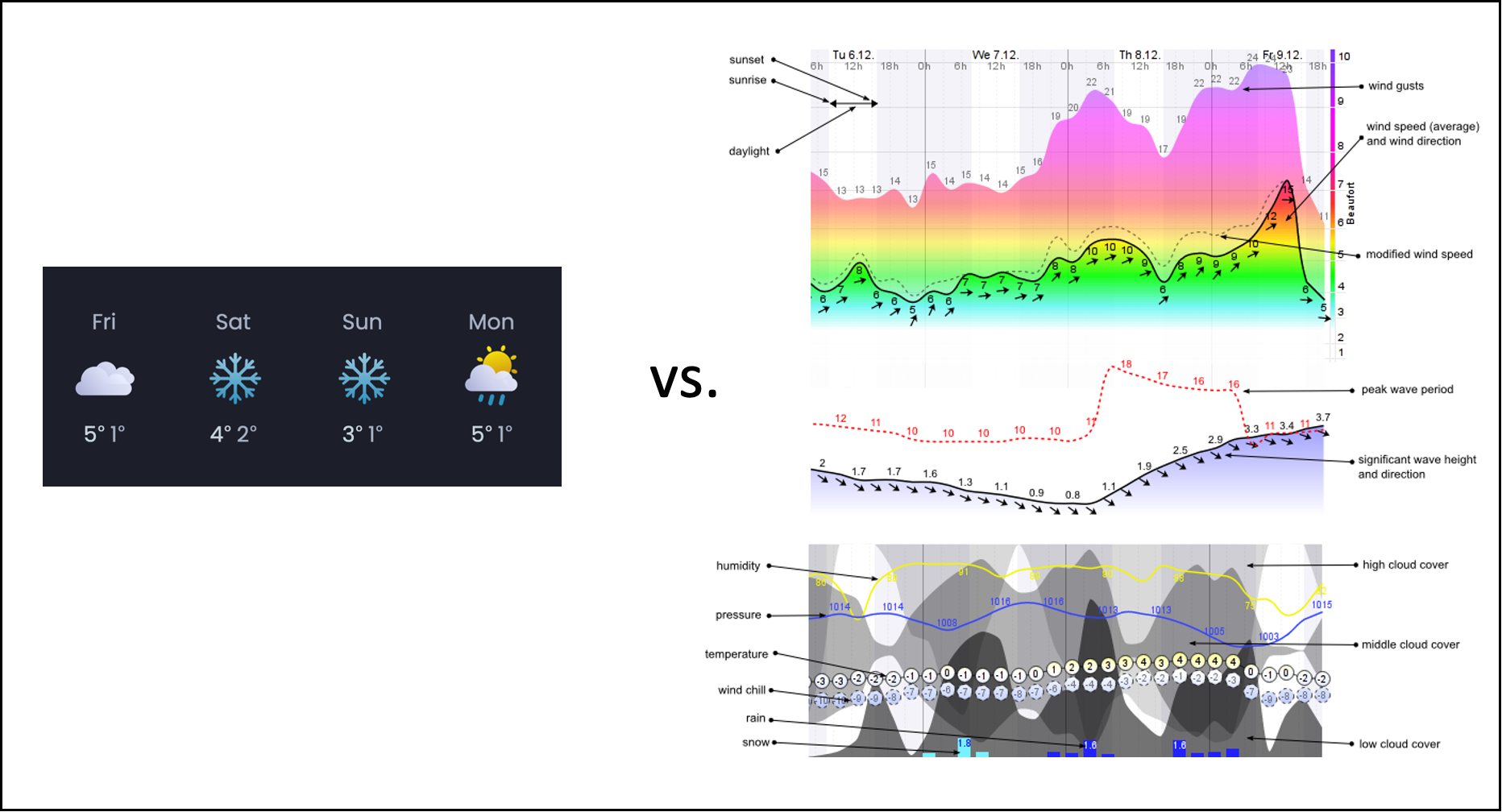

Discuss the example presented in Fig. 15 to clarify the concepts of degree of constraint, dimensionality of metric and level of description from Fig. 14.

Fig. 15 Two weather forecast differing in dimensionality of measurement, level of description and degree of constraint.#

Next, think back to the steps in computational ethology presented during the first lecture, and try to find examples for each of the axis in the behavioral space described in Fig. 14. Try using examples from your own research, as well as typical or every day examples.

Degree of constraint#

Animals can be freely moving in their natural environment, or in an experimental arena, or constrained to a skinner-box or even head-fixed to the apparatus.

…

Dimensionality of measurement#

Animal Behavior could be assessed every day to ensure welfare, or every hour to track behavioral patterns. Camera traps could take images every minute, or video recordings could use a frame rate of 10Hz, 30Hz, 100Hz or +170 pictures per second.

In addition to the added resolution, experiments can be recorded with multiple cameras from different perspectives, and combined with additional measurements such as noise level, illumination, key responses, as well as physiological and neural activity.

…

Level of description#

From data collection through data analysis and to the discussion of results the level of description should increase. Starting with the very specific data point in your experimental setup to wider implications for behavior and cognition.

…

Quantification of Animal Behavior#

Quote

“Behavior is a particularly hard problem. It is a complex, high dimensional, dynamical and relational phenomenon with no clear separation of scales. […] Behavior is a natural continuum in which some of the most challenging questions of physics, biology, psychology and the social sciences converge.” - Gomez-Marin et al., 2014

From continuous to discrete, and back#

Maybe two of the most pressing problems in the quantification of animal behavior are the continuity of time on the one hand, and the ever increasing degree of detail, i.e., dimensionality of behavioral data. These topics will be covered separately in the last two lectures on The Problems of Spacetime and Measuring in Multidimensional Space. For now, the important thing will be to understand and acknowledge these difficulties. Both time segmentation in discrete units and dimensionality reduction have the same goal to increase the level of description by aggregating information into meaningful units of behavior.

Prior to computational ethology, the individual scientist was responsible to perceiving information (aided or unaided), processing and maintaining it in memory for a while and aggregating it to a specific behavioral category or event. Problems with this method are the subjectivity of the researcher, proneness to human errors in perception and judgement, and the irreversibility of this classification. With machine learning techniques (see next lecture on Classification of Animal Behavior) this classification is not only statistical and data-driven, but reversible. This makes ethograms highly descriptive on an abstract level, while maintaining all the details, i.e., the high dimensionality of the data.

Some statistical methods#

Computational Ethology is still a very recent field of research, and the high variety of analysis methods used today still need to be standardized and established among research groups. Some of these statistical methods to quantify behavior will be discussed at a later stage during data analysis exercises in python. For now, it may be only necessary to understand that there exist different methods to transform low level and high dimensionality data into higher level, lower dimensionality representation. Some of these are segmentation, clustering or lower dimensional embeddings, and descriptive statistics such as covariance matrices or distances between distributions of continuous kinematic variables.

Literature#

Gomez-Marin, A., Paton, J. J., Kampff, A. R., Costa, R. M., & Mainen, Z. F. (2014). Big behavioral data: Psychology, ethology and the foundations of neuroscience. Nature Neuroscience, 17(11), 1455–1462. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3812